TOP 10 Exhibitions in 2024

-

Theaster Gates: Afro-Mingei, Mori Art Museum /「シアスター・ゲイツ展:アフロ民藝」、森美術館

-

Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now, Rubin Museum

-

Louise Bourgeois: I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful., Mori Art Museum /「ルイーズ・ブルジョワ展:地獄から帰ってきたところ 言っとくけど、素晴らしかったわ」、森美術館

-

8th Yokohama Triennale “Wild Grass: Our Lives”, Yokohama Museum of Art, etc. / 第8回横浜トリエンナーレ「野草:いま、ここで生きてる」、横浜美術館等

-

Modern Images of Ancient Clay Figures, MOMAT /「ハニワと土偶の近代」、東京国立近代美術館

-

Café de Chino – How Dear Things Are Absent, Hong Foundation /「咖啡奇諾 —— 珍貴的東西是多麼的缺席」、洪建全基金會

-

Yin Xiuzhen: Piercing the Sky, Power Station of Art /「尹秀珍:刺天」、上海当代藝術博物館

-

Cao Fei: Tidal Flux, Museum of Art Pudong /「曹斐:潮汐宙合」、浦東美術館

-

「100年後芸術祭 山武エリア」、山武市内

-

Yoshiaki Kaihatsu: ART IS LIVE―Welcome to One Person Democracy, MOT /「開発好明 ART IS LIVE ―ひとり民主主義へようこそ」、東京都現代美術館

-

[Honorable Mention] Step on the Threshold, Chinretsukan Gallery (TUA) & Surrounding Area /「敷居を踏む Step on the Threshold」、東京藝術大学大学美術館陳列館&周辺エリア

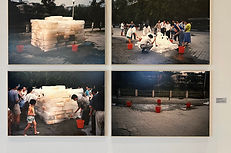

Afro-Mingei: A Convergence of Cultural Narratives

Rocio Cruz Toranzo

Chicago-born Theaster Gates rose to prominence as the art world recognized the Afro-American community's voices, with a vast multidisciplinary creation combining not just sculpture and ceramics, but also design, fashion, performance, and music; combined at its full expression in his revitalization projects in Chicago where abandoned buildings are reinvented as public art hubs. This experience converges with the deep influence that Japanese cultural and craft traditions have had on the artist over the past two decades, with 2024 being a suitable moment to debut with a great solo show in Japan.

Theaster Gates: Afro-Mingei exhibition, at Mori Art Museum, unfolds as a curated journey, presenting a range of artifacts installations —from traditional tools and textiles to modern reinterpretations—that together narrate a story of cultural convergence. Each piece is imbued with historical resonance and a contemporary sensibility, whereas also pieces supposed to be created by artists are fictional creations as part of the staged experience, inviting viewers to re-examine notions of authenticity, utility, and artistic expression

What does this unique expression “Afro-Mingei” mean? Many visitors were able to decipher it in different ways. The juxtaposition of African design motifs and aesthetics with the subtle, refined sensibilities of Japanese mingei craftsmanship creates a dynamic interplay that is visually arresting and conceptually stimulating. One of the most striking aspects of Afro-Mingei is its redefinition of beauty. The exhibition posits that beauty is not solely the domain of high art but is also embedded in the functional and the quotidian, offering a dialogue that challenges conventional boundaries while celebrating the inherent beauty of everyday objects, re-envisioned through this cross-cultural lens and elevated to symbols of shared human experience.

The spatial arrangement within the Mori Museum further amplifies the exhibition’s thematic ambitions. Thoughtfully designed pathways guide visitors through a series of vignettes, each section emphasizing a different facet of the cross-cultural dialogue. Informative placards and interactive displays provide historical context and personal narratives, allowing for an immersive experience that is both educational and emotionally engaging. As I moved through the exhibit, I was continually struck by how the presentation encouraged a meditative engagement with the works, inviting me to pause, reflect, and draw my own connections between seemingly disparate cultural artifacts.

From a curatorial perspective, Afro-Mingei is an exemplary innovative practice model. It deftly navigates the complex terrain of cultural representation, addressing potential issues of appropriation while fostering a respectful exchange between traditions. The exhibition’s narrative is not didactic but rather open-ended, prompting visitors to interrogate their preconceptions about heritage and modernity. This balance of reverence and critical inquiry is a testament to the thoughtful curatorial decisions behind the show.

In conclusion, Afro-Mingei at Mori Museum is a powerful exploration of the universal language of craftsmanship. It celebrates the dialogue between African and Japanese traditions by reimagining everyday objects as vessels of cultural memory and artistic innovation. My experience at the exhibition was both intellectually enriching and profoundly moving, reaffirming the belief that art—in all its forms—possesses the transformative power to bridge cultural divides and inspire new ways of seeing the world.

Theaster Gates: Afro-Mingei, Mori Art Museum

2024.4.24 [Wed] - 9.1 [Sun]

撮影:田中直子

Installation View, Mori Art Museum, 2024. Photography: Rocio Cruz Toranzo

シアスター・ゲイツ アフロ民藝

タニグチアスカ

ゲイツが代表的な作家として知られるブラック・アートは、その名が冠する通り黒人文化を根幹に制作されたアートを指す。彼の大きな特徴は幅広いメディウムを横断しながらブラック・アートを実践している点だ。展示構成においてもブラック・アートの文脈は意識され、黒人史や黒人文化についての書籍・雑誌などを自由に閲覧できるブックラウンジが設けられた。しかし展覧会全体は、ゲイツの制作におけるアイデンティティをブラック・アートに規定するのではなく、生と結びつく精神性に見出そうとしていたと考えられる。そしてその精神性は陶芸に最も現れていると解釈されていた。

本展には至るところにゲイツの制作と陶芸の関係が散りばめられている。

足を踏み入れた最初の「神聖な空間」では、天井の高い空間に対し作品は互いに距離をとって配置されていた。鑑賞する際は作品と一対一で向き合わなければならない。驚くべきは「神聖な空間」の床一面に敷き詰められた1万枚を超えるタイルも作品だということだ。関係を設えられた作品に比べ、足元に広がった膨大な数の陶芸作品は作家の無名性を感じさせる。

ブックラウンジとビデオ作品を挟み、「ドリス様式神殿のためのブラック・ベッセル(黒い器)」でブラックネスのアイデンティティを陶芸作品に反映させようと試みている様子もみられた。黒人文化圏に留まらずさまざまな民族性を取り入れたフォルムが特徴的な作品群だ。それは民族性やブラックネスをモチーフとする制作ではなく、陶芸には自らの生をどう反映させられるか確かめる実践であった。そのあとには年表で埋め尽くされた部屋が続く。年表には民藝の歴史やゲイツの初期プロジェクト、ヤマグチ・インスティテュートの主人公である架空の人物・ヤマグチにまつわる事柄も記載されている。

こうして「アフロ民藝」でタイルと同様に再び大量に見せられる「小出芳弘コレクション」はもはや来場者にとって無名作家の作品群ではない。作ることでそこに存在した生がありありと迫ってくるように感じられた。

最初と最後で陶芸作品に対する感じ方が変化するのは、ブックラウンジのあとに位置していたビデオ作品の力が大きい。「避け所と殉教者の⽇々は遥か昔のこと」「嗚呼、風よ」である。ビデオ越しであれど生身の肉体が登場する数少ない作品だ。ゴスペルの歌詞を用い、肉体を行使して行われたパフォーマンスの記録は、日本で感じることが稀有な、身体の芯で魂がふるえる感覚を引き起こす。「無名の職人が作った作品に敬意を払いつづける」という民藝の精神にゲイツは共感を示していた。それはその人物の生の痕跡に敬意を表すこと、有名無名に関係なく生そのものを祝福する行為でもある。ブックラウンジの隣のビデオ作品はゲイツがなぜ民藝の精神に共感を示したか、彼自身のアイデンティティと民藝の精神にかけて横たわる、「生」への態度に通底したなにかを来場者に直観的に伝えるものであった。

シアスター・ゲイツの人間そのものが、彼の実践を通して深く理解できる展示構成だったように思う。

シアスター・ゲイツ展:アフロ民藝

2024.4.24(水)~ 9.1(日)

https://www.mori.art.museum/jp/exhibitions/theastergates/index.html

シアスター・ゲイツ《アフロ民藝》、2024、インスタレーション、展示風景、撮影:タニグチアスカ

Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now

Benjamin Korman

This exhibition was monumental not just in its scale or its diversity of objects and narratives, but in its embodiment of those narratives. The Rubin Museum has been the premier site in Manhattan for the collection and display of historical and contemporary Himalayan art objects for about two decades; this is the final exhibition in the space as it passes the threshold from physical museum to a closed collection, available for object loans, the curation of traveling exhibitions, and “digital” exhibitions and experiences.

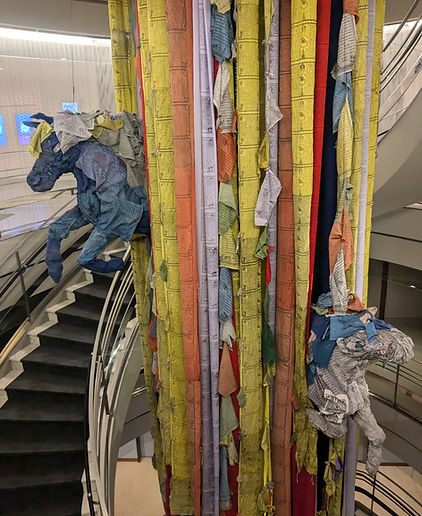

The exhibition, titled Reimagine because it prioritizes contemporary works from artists either based in the Himalayas or living in the Himalayan diaspora, occupies the three top floors of the building. A single artwork connects each floor: The Windhorse (lungta) by Asha Kama Wangdi and the team at VAST Bhutan hangs like a chandelier throughout the central spiral staircase. Made from discarded plastic prayer flags found in the streets of a Himalayan city, equine figures seem to burst from the draping mass, releasing themselves into a far away and unseen world. It is a metaphor for letting go, which Rubin visitors will soon have to do—and the soon-to-be laid off staff at the museum will have to do, as well.

Not as immediately obvious, the staircase is the site for a second artwork by the sound installation artist John Tsung. 神代 (Divine Generation) involves a system of electricity-sensitive cables wrapped around the handrails and sneaking further and further into the skeleton of the physical structure. The impulses they receive can only be understood by touching a rock sitting atop a podium. Placing your hand on it allows you to experience the collective sounds and waves of the environment above, below, and around you. It is a shocking sensation.

Other artworks touch on topics like natural disasters; a lost sense of identity as Himalayan people spread further and further away; personal stories and family histories; religious mythologies; references to historical objects, rituals, and gods; and more. Among the contemporary works are mandalas, spiritual objects, and valuables reaching back millennia.

The exhibition is a fitting end to a unique museum. It is hard to say what will happen next, or if this wide-ranging community of artists and historians will ever have a space to spotlight their culture so far away ever again

Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now

The Rubin Museum of Art, New York

March 15, 2024–October 6, 2024

The Windhorse (lungta) by Asha Kama Wangdi and VAST Bhutan, 2024. Photo by Benjamin Korman

Louise Bourgeois: I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful

Wang Yilin

When you stroll into Roppongi Hills, you will always notice the huge spider sculpture standing in the square. Its curved legs firmly cover the curious eyes of tourists like a web. This is Louise Bourgeois's public art work Maman. Following the trail of spider silk, you can come to the large-scale solo exhibition "Louise Bourgeois: I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful" that was exhibited at the Mori Art Museum from September 2024. This exhibition is the most comprehensive survey of Bourgeois's work ever in Japan, cleverly examining the intersection of personal trauma, institutional memory and spatial narrative. Through careful planning, the exhibition creates a psychological terrain that reflects Bourgeois's complex emotional landscape while sparking contemporary dialogues about trauma, identity and healing.

The exhibition's tripartite organization - "Do Not Abandon Me," "I Have Been to Hell and Back," and "Repairs in the Sky" - constructs a narrative arc that transcends mere chronological presentation. This curatorial strategy effectively transforms personal psychological terrain into universal human experience, with intermediary "column" spaces providing crucial historical context through early works.

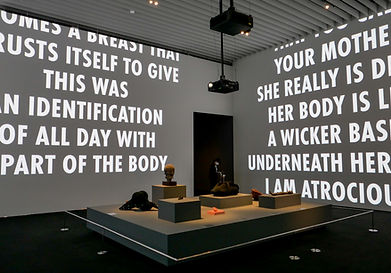

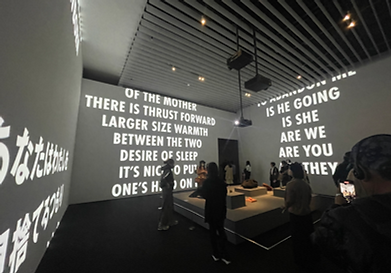

Of particular significance is the exhibition's innovative integration of archival materials with contemporary interpretive frameworks. The inclusion of Jenny Holzer's video installation, projecting Bourgeois's psychoanalytic writings and dream diaries onto the gallery walls, creates a profound temporal dialogue between past and present. This curatorial decision not only amplifies the emotional resonance of Bourgeois's work but also situates it within current discourse on psychological trauma and feminist narrative. The strategy recalls but transcends similar approaches seen in Holzer's 2022 exhibition "The Violence of Handwriting Across a Page" .

The exhibition's material diversity - spanning sculpture, painting, installation, and textiles - demonstrates Bourgeois's technical versatility while emphasizing thematic continuity. The Asian premiere of her early paintings provides crucial context for understanding her artistic evolution, while the strategic placement of works creates a psychological labyrinth that visitors must navigate. This spatial choreography transforms the institutional space into an active participant in the narrative, rather than a neutral container.

Louise Bourgeois: I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful.

2024.9.25 [Wed] - 2025.1.19 [Sun]

Louise Bourgeois: I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you it was wonderful. 2024, Installation View, Photography: Hasegawa Kenta

The revenge of the mother in

Louise Bourgeois: I Have Been to Hell and Back. And Let Me Tell You, It Was Wonderful

Lyudmila Georgieva

Louis Bourgeois’s Maman has been a landmark of Roppongi Hills since 1999—a nightmarish, towering spider imposing itself on the sleek, commercial landscape. For the artist, however, this was a figure not of horror but of nurture, closely linked to motherhood. Like a spider, the mother entangles her family in shared time and space. A signature of Bourgeois's work, Maman speaks through its physicality about care and confinement, trauma, and vulnerability.

In 2024, the Mori Museum of Art opened the first retrospective of Louis Bourgeois in 27 years: Louise Bourgeois: I Have Been to Hell and Back. And Let Me Tell You, It Was Wonderful. The exhibition similarly centered on raw materiality, family, and the artistic sublimation of trauma, showcasing 106 artworks across various genres. While Bourgeois worked across a wide range of media, she is primarily renowned as a sculptor, and the curation effectively supports this view. Every piece in the exhibition is approached in a sculptural manner that shapes the space around it.

With a similarly clear curatorial perspective, the exhibition chose to present Bourgeois's more-than-five-decade-long career not through its chronological development but rather through a strong thematic narrative. The works are divided into three chapters, forming a visible dialectical progression. The first two chapters take a biographical approach to interpreting Bourgeois’s art. The first examines her relationship with her mother, marked by a fear of abandonment and anguish from her untimely death. The second looks at the simultaneous resentment and care she felt towards her father.

The third chapter resolves this tension by expanding the perspective on Bourgeois's art through a methodological study. It explores the distinctive symbiosis of psychoanalysis, feminism, and artistic practice, through which Bourgeois constantly upholds the power of sublimation of the unconscious into art. Starting with the Surrealists post-World War I, most artistic explorations of the unconscious rely on desublimation—stripping away cultural transpositions and revealing the unconscious drives. Bourgeois’s firm belief in the power of artistic transformation, therefore, stands out.

While two columns in between the chapters provide more historical perspective, the first, Fallen Women, notably showcases the famous Femme Maison early series; most of the pieces on display are made in the final decade of Bourgeois’s life, after 2000. As a consequence, works with similar formal and thematic characteristics are spread throughout the space. Again and again, the viewer encounters distorted and fragmented bodies, nudes enmeshed in an embrace, body parts in various states of attachment, infants still feeding from their mothers, and hanging heads in confined rooms.

Working within sublimation doesn’t hinder Bourgeois's artistic language, which bursts with organic materiality, unabashed (though not necessarily erotic) sexuality, and a willingness to forgo beauty in favor of eerie depictions of life. Due to the repetitions, there seems to be no formal progression—only a deeper understanding of the surroundings. Like a repeated disturbance of the artist's trauma, the exhibition traps viewers in an uncanny world, forcing them to face the disturbing bodies that populate it.

The first room of the exhibition marks the transition into Bourgeois’s surreal, dark universe. It features sculptures of exaggerated and absurd bodies at the center, surrounded by three wall projections (by Jenny Holzer) displaying Bourgeois’s psychoanalytic impressions on family and human connection, moving from bottom to top. These moving white letters create a sense of disorientation, stunning the viewer. The works—a double-handed arm, double-ended penis, two-faced head—intensify the impression of flesh distorted and defiant of its surroundings.

Louise Bourgeois was one of the first artists to be exhibited under the label of abjection at the landmark 1993 Whitney exhibition Abject Art: Repulsion and Desire in American Art. The term, popularized by Julia Kristeva in Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (1980), refers to the anxiety, repulsion, and horror evoked by encounters with objects or experiences—such as blood, dirt, or death—that disrupt the boundaries of subjectivity. When introduced into art practice and criticism in the early 1990s, abjection became closely tied to feminism, manifesting as representations of the female body as deformed and repulsive, assaulted by patriarchal society. Within this framework, Bourgeois’s exploration of the feminine body as both a site of trauma and resistance stands out as particularly significant.

Bourgeois's exploration of abjection aligns closely with Kristeva’s theory. For both, the mother’s body is the primal site of abjection, rejected when the infant asserts its subjecthood in the act of separation. For both, this process is difficult and deeply traumatic. For both, the mother is vital yet threatening.

Opening the first chapter of the exhibition, dedicated to the child-mother relationship, is a sculpture titled The Good Mother (2008). A woman is giving her milk away in five streams (for Bourgeois, the number five symbolizes the family). The figure is simultaneously submissive—kneeling with a downcast gaze–yet her strained pose and flowing milk exude strength and will. The nurture symbolized by the milk is combined with pain and exploitation, as well as power and might. Throughout the exhibition, the female breast emerges as a crystallized image. Bourgeois' bodies are consistently covered in spherical forms. Resembling breasts or wombs, however, there is also a similarity to throbbing tumors or soars.

In the depictions of obsessive motherhood, the exhibition reaches its full potential of abjection.The Good Mother is followed by figurines and diagrams depicting Bourgeois’ difficult childbirth, which she attributes to her son’s reluctance to separate from her body. Next, the viewer enters a sectioned-off room titled Feeding, where a series of white and pink gestural paintings (gouache on paper) portray a fetus coming to full life within the womb. The repeating colors and images on the four walls envelop the viewer, sucking the air out of the already small space. Over and over, the paintings show the unborn child engulfed in the mother’s body, feeding off her indistinct flesh. Through sculptural, three-dimensional curation, Feeding creates a visceral sense of confinement, evoking a terror of being engulfed by the mother’s body, detained and passively nurtured until the distinction between the self and their surroundings disappears.

The power of Bourgeois’ depictions of motherhood stems from the constantly shifting perspective between mother and child. The viewer is thus made to empathize both with the exploitation of the mother’s body and with the infant’s painful metamorphosis into a full-fledged subject.

Bourgeois portrays the mother as embodying both love and dread. Her famous installation, The Destruction of the Father (1974), imagines a family dinner where the patriarch is dissected and eaten, while breast-like spheres once again line the floor and hang from the ceiling. The work subverts Freud’s myth of the origin of society, where the tyrannical father is killed by his sons, and his rule is abstracted into law. The Destruction of the Father portrays the killing not as a rational act of justice but as revenge. In the same room is La Filette (1968) – a singular latex sculpture of a flayed penis, its pushed-back skin revealing bubbling flesh underneath, tender and in need of (mother’s) care.

In its dialectical progression, the exhibition articulates Bourgeois’ critique of the psychoanalytic structure where the abjection of the maternal becomes a necessary cultural act. In psychoanalysis, this is symbolized by the distinction between the mother tongue, singular and held within the body, and the father’s language, shared and culturally productive. Bourgeois’ constant insistence on the mother aims to elevate the mother tongue in rejection of patriarchal domination, both familial and cultural. The patriarch is killed and eaten as revenge, while his penis is left defenseless—hung and flayed.

This revolt is not a regression to a pre-subjective, infant state. Instead, Bourgeois recuperates the feminine’s cultural power by refuting the necessity of the abjection of the mother’s female body. In other words, Bourgeois argues for the cultural potency of the mother tongue.

Subverting one of psychoanalysis' core tenets of societal and individual development, Bourgeois' art transcends the male-female divide, avoiding a mere reversal. In the first chapter, the mother gathers the family within her body, while in the second, the father’s power is sacrificed. The third section of the exhibition breaks this tension.

The works in the third chapter are less autobiographical and more analytical. They include Sublimation (2002), in which Bourgeois directly engages with psychoanalysis and outlines her method of artistic sublimation, and Ode à l'Oubli (2002), a collection of 35 fabric illustrations that pay tribute to the artist’s childhood in France and her family’s textile business. This section also features the vitrine Conscious and Unconscious—two structures, one rationally constructed and the other woven through five separate threads—representing an apotheosis of Bourgeois' belief in the productive power of the unconscious transformed in the artistic process.

As revolting as they can be, Bourgeois’ sculptures do not remain within the unconscious or the pre-subjective, natural state. On the contrary, she unrelentlessly argue for the possibility of the sublimation of the mother tongue into culture. Language, art, writing, philosophy, all usually associated with the father realm, are conveyed in Bourgeois art through the female, usually the mother’s body, refuting her necessary abjection in the process of subjectivation.

Series of Bourgeois’ sculptures could be described as contained chaos. The most striking of them is probably The Couple (2006), a towering aluminum sculpture, featuring two intertwined, spiralized bodies locked into an embrace. For Bourgeois, the spiral symbolized the interplay of dual forces, embodying a tense dynamic between freedom and control. The cultural emerges not as an imposed boundary or patriarchal hierarchy, but as a fragile structure that barely contains—and channels upwards—an otherwise destructive energy. This strenuous containment also appears in Bourgeois’ soft sculptures—bodies and body parts (mostly heads) stitched from fabric pieces. Though on the verge of bursting, they remain intact, held together by the threads of the artist’s imagination. In both cases, the chaotic force of nature, previously unassimilable and thus expulsed, is made productive through artistic form.

In the parallel of moving beyond the male-female simplified divide, the last section of the exhibition also moves away from the somewhat reductive interpretation of Bourgeois’ art through autobiographical accounts of trauma.

Similarly to moving beyond the simplistic separation of male and female, in its last chapter, the exhibition also moves away from the reductive interpretation of Bourgeois’ art as autobiographical accounts of trauma. Perhaps that’s also the reason why more recent works were predominantly chosen for the retrospective. Through the achieved balance, they better showcase Bourgeois’ distinctive understanding of psychoanalysis and her specific approach to feminism. The resolved dialectical tension, the achieved precarious balance between trauma and sublimation, mother and child, female and male, asserts Bourgeois’ unique artistic approach and deserved place in art history.

Louise Bourgeois: I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful.

2024.9.25 [Wed] - 2025.1.19 [Sun]

Louise Bourgeois: I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you it was wonderful. 2024, Installation View, Photography: Lyudmila Georgieva

The 8th Yokohama Triennale "Wild Grass: Our Lives"

Wang Yilin

我以这一丛野草,在明与暗,生与死,过去与未来之际,献于友与仇,人与兽,爱者与不爱者之前作证。

Between light and darkness, life and death, past and future, I dedicate this tussock of wild grass as my pledge to friend and for, man and beast, those whom I love and those whom I do not love.

——Lu Xun, Wild Grass

The 8th Yokohama Triennale ”Wild Grass:Our Lives”, transforms three key venues – the newly reopened Yokohama Museum of Art, the former Daiichi Bank Yokohama Branch, and BankART KAIKO – into a profound exploration of human resilience and adaptability. Curators Liu Ding and Carol Yinghua Lu have crafted an exhibition that transcends the boundaries of traditional art exhibitions, pondering the relationship between individuals and history, individuals and the times in the turbulent present, and painting a portrait of thought for our times.

The exhibition draws inspiration from Lu Xun’s 1927 poetry collection Wild Grass, using this powerful metaphor to examine how communities persist and adapt in challenging times. The curatorial vision unfolds in seven carefully constructed chapters, each offering a unique perspective on survival and rejuvenation. This framework is particularly effective in the Yokohama Museum of Art's Grand Gallery, where a commissioned “camp” transforms the institutional space into a contemplative environment for exploring impermanence and adaptation. Joar Nango’s “Ávnnastit/Harvesting Material Soul” stood out for its investigation of the relevance of indigenous culture in architectural discourse and architecture today.

The exhibition’s strength lies in its emphasis on community engagement and participatory art. Lieko Shiga’s “Emergency Library” focuses on the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and nuclear disaster, creating a powerful space for collective memory and healing. Similarly, Susan Cianciolo’s “RUN Café” reimagines the gallery as a social hub, effectively breaking down barriers between art and everyday life. These installations demonstrate how art can foster meaningful conversations about shared experiences and recovery.

A highlight of the exhibition is a mini-retrospective dedicated to Tomiyama Taeko (1921–2021), whose politically charged works remain as impactful today as they were in her time. Known for her print series supporting South Korea’s democratization in the 1970s, Tomiyama later turned to Surrealist painting, reimagining Asia as a mythical landscape filled with gods, fairy-tale creatures, and legendary animals. Her work embodies Lu Xun’s enduring sentiment: only by confronting the darkness can we truly see the truth.

Through this thoughtful exhibition, “Wild Grass” offers a timely reflection on what it means to survive and thrive in today’s world. The exhibition successfully demonstrates how individual stories connect to larger narratives of collective endurance, making it a particularly relevant exploration of community resilience in the current global context. It reminds us that survival and resilience are shared experiences, shaped by our connections to each other and our environment.

8th Yokohama Triennale “Wild Grass: Our Lives”

March 15 – June 9, 2024

Resilience and Crisis

— Wild Grass: Our Lives, 8th Yokohama Triennale

Able Zhang

Curated by Carol Yinghua Lu and Liu Ding, the 8th Yokohama Triennale, Wild Grass: Our Lives formulates its title and philosophy from Lu Xun’s prose-poem collection Wild Grass (1927), a work written during a turbulent and unsettled period of Chinese modern history. In his writings, Lu Xun’s “wild grass” symbolizes the vulnerable humanity that persists stubbornly even in the times of the most darkness. Inspired by this metaphor, this exhibition frames social instability, political disorder, migration, and global uncertainty as conflicting challenges merged into the fabricating process of everyday life. Nevertheless, rather than offering a sort of “cheap optimism,” this exhibition celebrates what Lu Xun calls the “quiet resistance of survival”—small yet resistant acts of life that endure through war, oppression, and disruption.

Why does this “quiet resistance” in Lu Xun’s prose poems still matter in today’s world? The curators have spent the entire exhibition to demonstrate the significance of seeking such spirit of wild grass in the contemporary society—by creating a landscape of crises. The grand hall of Yokohama Museum of Art is dramatically transformed into an improvised camp-like space. Tumbledown tents, wooden sheds, and skeletal sculptures spread across multiple floors of platforms, immediately bringing audiences into a sense of dislocation. What also stands out in our vision would be Unearthed Leaves by Sandra Mujinga. These fabric figures are like giant creatures in an invisible form—only their hoody somehow appears above their heads. There are also constant noises coming from Open Group’s video Repeat After Me, across from the hall, in which Ukrainian refugees mimic the terrifying sounds of war. On the same side, you can slightly see Lieko Shiga’s photographic series in the upstairs hallway, which mixes images of fire making and night forests. This multi-sensory installation evokes a “continuous crisis mode.” When Atsuko Tanaka’s Work (Bell), triggered by someone, rings across the entire museum space, the surrounding fear and dread builds, presenting a world where political chaos and environmental disasters have already arrived here in our current lives. By turning the entrance gallery, together with elements from the upper floor, into a nightmare-like stage setting, the curators foreground crisis as an internal mindset which the audiences must accompany with from the very beginning.

The spatial design not only corresponds with the concept of crisis but also works well on reflecting the continuity and ties between different artists and gallery spaces. For example, a gallery room dedicated to Taeko Tomiyama’s 1950s prints and paintings of coal miners in Kyushu (entire Gallery 5) is placed in a closed relation in viewing order/flow with British artist Jeremy Deller’s 2001 video (next to the exit of Gallery 4), The Battle of Orgreave, which captures a violent clash between miners and police in 1984 England. Despite of the differences in medium and context, these two bodies of work speak across time: Tomiyama’s frustration with representing miners’ struggles correlates with Deller’s dramatic re-staging of the labor history. Thereby, these works are not isolated aesthetic production but engaged with the real world, and that artists across eras have combined these real issues together in conversation. By treating the exhibition itself as a kind of essay composed of artworks and archives, Lu and Liu encourage audiences to identify patterns and draw connections with their own memories, identities, backgrounds, and values, effectively turning the audience into active interpreters of the concept of crisis.

On the other hand, “quiet resistance” does not merely signify crises. There are a lot of moments of resilience also implied beyond the surface of chaos and environmental disasters. We can see plenty of disappointments and desperate situations in diversified eras and regions, yet we can always also see how artists respond or document others’ responses towards those situations, like those hand-painted Vietnamese protest signs in Your Bros. Filmmaking Group’s work Ký Túc Xá (Dorm). The entire exhibition is like a process of meditation and reflection on how individuals and communities persist through adversity and difficulty—how they negotiate with the crises yet never compromise their principles. The exhibition repeatedly returns to images of resilience and acts of resistance, both quiet and wild. Lu Xun’s influence is probably here. Just like his writings urged us to confront desperation and find a way out of “complete darkness,” the exhibition acknowledges the potential risk of nihilism and cynicism yet persists in continuing to care.

Wild Grass: Our Lives functions as both a mirror and a rethinking process on our ongoing surrounding socio-political moment—despite of the thriving capitalism, we are living in a unstable society that is filled with new forms of hierarchies and discriminations and is no better than Lu Xun’s world in the 19th and 20th centuries. From immersive spatial design to the delicate arrangement of artworks and historical context, the exhibition conceptualizes “crisis” as a condition that connects past and present, the personal and the collective. The selected artists respond to this theme with works that accomplish much more than merely representing issues of their own backgrounds—they engage us, the audiences, in their and our stories of war, migration, labor, censorship, and survival. Each of them illuminates a different aspect of resilience. By this, the exhibition’s power transcends the literal representation of wild grass: it stubbornly grows through the cracks and confronts darkness while still seeking, as what Lu and Liu declare, the “irrepressible force of life.” Moreover, even when the fire comes and burns the grassland, they will always find the way to return when spring arrives again.

1. MOVIUS, Lisa. “We must survive: Yokohama Triennale entwines stories of darkness and resistance,” The Art Newspaper, accessed March 3, 2025, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/06/07/yokohama-triennale-2024-review. Web.

2. HEISER, Jörg. “8th Yokohama Triennale, ‘Wild Grass: Our Lives’,” e-flux Criticism, accessed March 10, 2025, https://www.e-flux.com/criticism/611602/8th-yokohama-triennale-wild-grass-our-lives. Web.

3. FITE-WASSILAK, Chris. “8th Yokohama Triennale, Reviewed,” ArtReview, accessed March 12, 2025, https://artreview.com/yokohama-triennale-wild-grass-our-lives-2024-review-chris-fite-wassilak/. Web.

8th Yokohama Triennale “Wild Grass: Our Lives”

March 15 – June 9, 2024

Installation View, Yokohama Museum of Art, 2024. Photography: Able Zhang

Modernity uses of the past in

Modern Images of Ancient Clay Figures (2024, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo)

Lyudmila Georgieva

The Modern Images of Ancient Clay Figures exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art features works—ranging from art pieces and archival documents to video games—that reference ancient Japanese designs and imagery from the Jomon, Yayoi, and Kofun eras. Rather than just highlighting the archeological discoveries and research of ancient artifacts, the exhibition explores their interpretations and uses in the different periods of 20th-century Japanese history.

Modern Images of Ancient Clay Figures was organized alongside the Tokyo National Museum’s exhibition Haniwa: Tomb Sculptures of Japan. The latter marked the 50th anniversary of the designation of the Haniwa Warrior in Keiko Armor sculpture as a National Treasure. That exhibition showcased authentic Yayoi and Kofun burial objects as apolitical archeological achievements and evidence of ancient Japanese culture. In contrast, the curators of the Museum of Modern Art delved deeper into the political uses of the ancient artifacts. Curiously, while Modern Images of Ancient Clay Figures was not an obscure exhibition by any means, the Haniwa: Tomb Sculptures of Japan show attracted a visibly larger audience.

The Modern Art Museum exhibition begins with a Prologue section, Antiquarianism and Archaeology—A Leisurely Interest or Academic Study?, which explores the role of archeology in Japan. Introduced from the West in the early Meiji period, archaeology and other historical disciplines paradoxically propelled Japan’s modernization by studying the past through a distinctly European lens. Adhering to a Western model, the national state was legitemazed through its ancient origin. This contradictory link between the study of the past and modernization is explicitly highlighted in the exhibition’s introductory text and resonates throughout the entire display. The subsequent sections showcase how ancient Japanese imagery was used to advance various projects of modernity.

The first chapter, Unearthing “Japan”—Mythology and War, examines the rise of interest in Haniwa clay figures around 1940, leading up to the 2600th Anniversary of the Japanese Empire. The Haniwa symbolized national strength and the 'unbroken imperial line,' with their simple lines and strong forms representing the purity of the Japanese spirit. This section features archaeological curiosities, such as photographs and sketches, as well as historical recreations in paintings, films, and books, concluding with the mythologization of ancient Japan in support of the military imperial project.

Various commodities, such as game cards, postcards, and books, depicted a fictionalized version of Japan’s past to promote loyalty to the Japanese state among children. Similarly, idealized depictions of Kofun-era culture, such as the large screen Haniwa (Tsuji Kako, 1916), served to emphasize the continuity between ancient and modern Japan and propagate modern nationalism. This logic culminates in the combination of Haniwa imagery with the World War II Japanese army, as in Heaven’s Warrior (Koji Fukiya), painting a picture of a heroic Japan.

The first chapter effectively demonstrates how the modern Japanese state referenced ancient artifacts in art and popular media as a legitimizing tool. It shows how, during the first half of the 20th century, these artifacts were strategically employed to advance Japanese nationalism, fostering a clear distinction between Japan and other nations. There is a significant irony in this conclusion for anyone familiar with nationalist theory—a European invention used to justify colonialism and white supremacy.

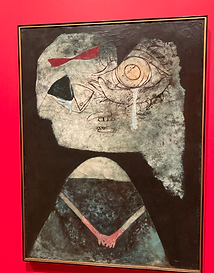

The second chapter, Unearthing “Tradition”—Jomon Period vs. Yayoi Period, focuses on the re-emergence of interest in ancient artifacts during the 1950s and 1960s. Beginning with the symbolic upturning of the soil, scorched by the devastation of World War II, and the subsequent emergence of numerous excavation sites, this section explores the changing meaning of those artifacts in the post-war context. The simple, strong lines that once signified the purity and strength of Imperial Japan came to be associated with modernist Western art movements. Exhibited are various experiments in cubism (Saito Kiyoshi’s Haniwa[1] (1954), Dogu[B] (1958)), abstraction (Hasegawa Saburo’s On the Bank of the Lake (1948) and Yoshihawa Jiro’s Face with Teardrop (1949)), and even Art Brut (Chokai Saiji’s canvas Haniwa (1959)).

The chapter explores two key aspects of the changing contexts in postwar Japan: formal artistic innovation and the re-orientation of Japanese society. Both were products of the country’s opening up in search of international connections after the years of wartime isolation and aggression. While in the first chapter, interest in the Haniwa figures was rooted in nationalism and isolationism, the second chapter illustrates their re-interpretation as a connecting point between Japan and the West.

This break with the past is presented through the so-called Controversies on Tradition—an artistic movement during the postwar period in Japan that shifted the perception of Japan’s origin from the previously hailed Yayoi era to the earlier Jomon period. This movement was marked with a growing interest away from Haniwa and towards Dogu figures—small human and animal figurines most likely representing nature and fertility. The Dogu figurines differ from Haniwa in their fluid lines and curved forms, thus offer a transition from the purity and severity of the Japanese military ideal to a more open and communicative imagery. At the end of the section, on a lit podium are displayed variety of small sculptures by Isamu Nocuchi, Okamoto Taro, Tatehara Kakuzo, and others. Featuring cubistic exaggerated bodies, simplified minimalist faces, non-pragmatic vessels, and other abstract objects, theses sculptures represent the 20th-century Dogu artifacts.

It is clear, however, that the art from this time continues to represent both Haniwa and Dogu imagery, without explicit difference between the two. More than a formal shift, the re-focusing of the past reflected a re-orientation of Japanese society after the war towards international cooperation.

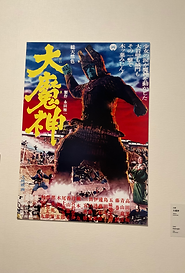

The third chapter of the exhibition, Digging Back to the Start—Artifacts in Our Surroundings, is also the shortest. It examines the 1970s and 1980s science fiction and occult boom in Japan, and the subsequent representations of Haniwa and Dogu-adjacent imagery in manga, films, and other mass-media products. Moving from national pride to artistic experimentation, the ancient form has become a cultural commodity, seemingly devoid of its previous deep political symbolism. Far from demythologization, this signifies the ancient imagery becoming part of a shared cultural arsenal, one that can be recalled and used as shorthand. The transition from archaeological achievements through political use and artistic reimagining to its eventual presence in popular culture is a cycle present in all three chapters, while simultaneously shaping the curation of the overall exhibition.

It’s notable that neither the Modern Images of Ancient Clay Figures nor the Haniwa: Tomb Sculptures of Japan exhibition comprehensively explain the differences between the ancient periods—Jomon, Yayoi, and Kofun (Haniwa are, in fact, Kofun artifacts). This may confuse the pedantic viewer or the archaeological enthusiast, and it is certainly a miss in an exhibition focused on Haniwa, as was the case with the National Museum show. However, in Modern Images of Ancient Clay Figures, this ambiguity highlights an important aspect of how ancient history is utilized in modernity. The focus is not on the formal characteristics of the artifacts themselves, but on the modern meanings they carry.

The abstract forms of Haniwa and Dogu came to symbolize purity in imperial Japan, openness to the West during the postwar reconstruction, and the rise of popular culture in the 70s and 80s. Writing during the Controversies on Tradition, Okamoto Taro’s essay “On Jomon Pottery” (1952) explicitly distinguishes between Jomon and Yayoi, favoring the former. While he describes the formal differences between the pottery of the two periods, the deciding factor in this shift was the lack of imperial symbolism on Jomon artifacts. Although Jomon pottery offered more formal dynamism compared to the clean lines of Yayoi (or Haniwa, for that matter), the positive interpretation of this dynamism marked a break with Japan’s military past and provided an opportunity to propose a new origin for Japanese culture—thus, reinventing Japanese modernity.

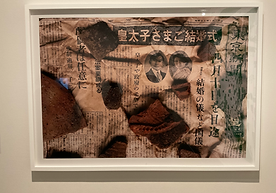

The exhibition ends with Tatsuki Masaru’s KAKERA (2019)—a newspaper page documenting the 1959 Crown Prince's wedding, held down by pieces of ancient pottery. Both the pottery and the newspaper page are damaged—broken, cut, and creased—referencing how the access society has to its past is always fragmented. With this piece as its conclusion, the exhibition argues for the possibility of a new re-interpretation of the past and the re-invigoration of tradition. As a museum primarily focused on curating historical exhibitions of art, MOMAT raises the question of the interconnection between past and present—how the past has shaped the present state, and how in turn, the present determines the past’s meaning.

Modern Images of Ancient Clay Figures

October 1-December 22, 2024

Modern Images of Ancient Clay Figures. 2024, Installation View, Photography: Lyudmila Georgieva

Remembering the Absent:

Café de Chino – How Dear Things Are Absent

Able Zhang

As an immersive art exhibition that reconstructs the white-cute zone within the gallery space, Café de Chino – How Dear Things Are Absent, by the Taiwanese artist duo Working Hard, transforms the gallery into a ghostly mid-19th-century Chinese café from Mexico. Through the rebuilt setting of the fading world of “cafés de chinos”—Chinese-operated cafés that once thrived in Mexico, the exhibition explores themes of migration, cultural hybridity, and collective memory. Walking into the exhibition feels like stepping on the time machine: the decorations, signs, and even lingering coffee scent remind the long past era that actually existed, yet the space is obviously lack of owners, staff, or customers—an empty site awaiting participants to join in. This careful staging immediately corresponds with the exhibition’s fundamental inquiry: how do we remember places and communities that have vanished, and what remains when these invaluable “dear things” are no longer present? The artist and curator of this exhibition has responded to the question with an affecting and pricking art experience that blurs history and memory, inviting audiences to engage with the traces of a fluid identity nearly erased by time.

In the 1950s of their peaking time in Mexico, Chinese cafés were brought into the collective memory of the local community as intercultural dining spaces where Chinese and Mexican influences merged. The exhibition space also shows this cultural hybridity with plenty of physical evidence—Chinese teapots and calendars sit alongside Mexican diner-style booths and Spanish signs, illustrating a mix of identities. Through this, the artist duo “navigates the relations between those intercultural dining places and their related immigrant history.” In other words, Working Hard uses this work to illustrate how migrant narratives and collective memories intertwine with each other and highlight the absence of these narratives under mainstream stories.

Although there might be a potential risk that the exhibition turns itself into a didactic visual history lesson at the first glance, the artist and curator have emphasized the diasporas’ experience and their collective memories by doing the opposite—excluding any existence of owners, staff, nor customers from the setting. The absence of actual people represents the silenced or overlooked voices of the Chinese-Mexican community in history, despite of the once thriving period of Chinese cafés. The exhibition asks audiences to imagine the untold stories of the owners, staff, and customers who inhabited these cafés. The quiet and empty quality of the space is surprisingly a reminder of those “forgotten or overlooked diasporas and their histories.” Thus, with the affective and atmospheric site created by the artist, the exhibition space serves as a living archive, mediating history through an experiential and fluid environment rather than through textbooks or informational tellings.

On the other hand, the stage-like set is delicately detailed, from the vividly delicious cakes served to the few coins on the table. The exhibition blurs the line between art and surrounding environment, enveloping visitors in a cinematic recreation of a café. The spatial storytelling is structured as a deconstructed film set. In fact, the space design echoes a movie production, with props and background arranged as if awaiting actors. Audiences become the only living “actors” on this stage, free to wander through the café’s different areas: antique tables with half-filled coffee cups, a counter with a register and menus, wooden dividers, and even an open-view kitchen in the back. Furthermore, what sets Café de Chino – How Dear Things Are Absent apart is how it actively invites audience participation in these cinematic recreations. Rather than just looking at a movie story from a God’s view, audiences enter and inhabit the space. On Thursdays during the exhibition period, the gallery even offered “self-service coffee” to visitors for a couple of hours, allowing people to literally taste the story (I do, however, think they should offer this taste for every visitor entered daily instead of merely limited Thursdays). This arrangement transforms audiences into participants—you could sip a cup of coffee while sitting in the vintage café booth, blurring the boundary between observing history and reliving it. Through such interactive elements, the exhibition becomes an immersive theater of memory. The usually passive act of viewing turns into an active, multi-sensory experience. These sensory takings ground the historical themes in body experiences, making the exploration of migration and diasporas not only intellectual but also instinctive.

In Café de Chino – How Dear Things Are Absent, history is not a distant thing compressed into archives, but rather it is a living experience recreated within the gallery space. The artist highlights what is lost when a cultural enclave fades away under neoliberal globalization. Yet, in that very act of highlighting the loss, Working Hard also momentarily reverses it reflexively: for the duration of the show, that lost world is present again, tangible and cherished. What’s more, this exhibition is a compelling example of how contemporary art can mediate history, turning a gallery into a living archive of collective memories. A space invites every participant to not only remember the absent but also write his/her/their own stories and reflect on his/her/their own connections to place, memory, and identity.

1. PENG, Jo Ying. “Working Hard: Café de Chino – How Dear Things Are Absent,” Hong Foundation, accessed February 28, 2025, https://hongfoundation.org.tw/events/19. Web.

2. TAKAMORI, Nobuo. “Café de Chino: A Realist Theater,” (title translated by Able Zhang), ARTalks, accessed February 28, 2025, https://talks.taishinart.org.tw/talks/79/38905. Web.

3. Working Hard. “Cómo están de ausentes las cosas queridas,” artworkinghard, accessed February 28, 2025, https://artworkinghard.wixsite.com/portfolio/featured-project. Web.

Café de Chino – How Dear Things Are Absent

2024.10.19 - 2024.12.21

Installation View, Hong Foundation, 2024. Photography: Able Zhang

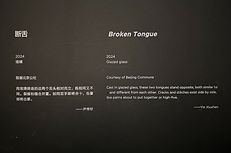

Broken Tongue(s) in Yin Xiuzhen: Piercing the Sky

Anqi Li

The Closing Talk given by Karen Smith on Yin Xiuzhen’s early works and on contemporary art in 1990s China helped illuminate the discomfort I felt after visiting Piercing the Sky (figure 1). Smith mentioned how, in the ’90s, artists created spaces out of nowhere to present artworks that responded to the rapid changes in China—changes they both witnessed and felt compelled to articulate. As Yin noted in her interview with curator Hou Hanru, they valued the “vein between true reality and the artwork.” Now that many institutions (museums, art centers, and on) have been built to host large-scale touring exhibitions like Piercing the Sky, is that vein still there? Does art still connect to the reality outside the gallery? In that sense, the work Broken Tongue (2024), made with cracked fleshy glass (figure 2), rather than the eponymous Piercing the Sky (2024), better captures my experience of this exhibition.

From a curatorial standpoint, the exhibition Piercing the Sky makes good use of the Power Station of Art, Shanghai (PSA)’s repurposed industrial space (figure 3). Still, the didactics present puzzles, suggesting things that cannot be named. Typically, the curator writes the didactics as a mediating voice, leaving room for interpretation. Yet here, the wall texts are Yin’s own words. As the creator, her statements have the final say and hover over the exhibition like an oracle (figure 4). However, her words here seem vague and confusing, even broken at times. To help with my confusion, I found myself reaching back to Yin Xiuzhen’s 2015 book (figure 5) for the missing information, despite most works on view were created in 2024. This review is my attempt to unravel these puzzles in Piercing the Sky.

Open Entrance at PSA Shanghai

Like many converted factory spaces (such as Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto or Venice’s Arsenale), the PSA features high ceilings and an expansive, open layout overlooking the Huangpu River—its industrial past is a story for another day. This exhibition starts off with an open arrangement, featuring Flying Machine (2008), Piercing the Sky, and Sky Patch (2024) (figure 6). Among these, Sky Patch—with sprawling colorful clothes floating above the structure—immediately commands attention (figure 7). Continuing an approach she first used in Dress Box (1995), Yin has incorporated old clothing, a material linked to childhood lessons from her mother, who worked in a clothing factory. Clothes, she says, serve as a “second skin,” reflecting “identities, classes, tastes, cultivation, and different cultural orientations.” She adds, “[o]nce wrapped around warm bodies, they still radiate spiritual warmth when they enter my work.” In Sky Patch, though, the clothes hang so high that their warmth feels out of reach.

This sense of distance persists in Action and Reflection in Shanghai (2024) and 1080 Breaths at PSA Shanghai (2024) where visitors are kept at a remove by physical barriers, with people’s donated shoes and breaths separated from people. While Yin’s interest in personal experiences continues, these works contrast with her earlier pieces such as Washing the River, which invited passersby off the street to participate spontaneously (figure 8). Participants here were recruited via the gallery’s WeChat account—limiting engagement to a particular subset of art followers. This is reminiscent of Shanghai’s tendency toward curated representation of certain classes, reminiscent also of April 2022, when coverage of the city’s pandemic hardships overshadowed others in smaller towns and cities. But that, again, is another story.

Nearby, handwritten messages attempt to rekindle warmth by sharing the shoes’ backstories. I noticed, however, that some of these stories repeat, suggesting they may not be entirely handwritten (figure 9). Distracted by this doubt, I find myself disengaging from the works. Instead of evoking a sense of intimacy and personal history, they begin to feel more like a repository of discarded objects—an assemblage of remnants without clear emotional resonance. The accumulation of shoes and breaths, once intended to embody lived experiences, now seems depersonalized, reduced to mere quantities. Yin herself has observed this in rapidly developing places like China, “fashion changes incredibly quickly, [… and people’s] choice of styles of clothes, and their compulsion to abandon old ones, demonstrate their attitude towards life and the world.” Yet here, the act of collecting and displaying these clothes seemed to strip them of their pasts. In 1080 Breaths at PSA Shanghai, each shirt is tightly knotted, squeezing away its residual human warmth into thin air—sealed off, inaccessible to those now looking in (figure 10).

Although clothing remains central in Yin’s work, the clothes originally wrapped around Flying Machine—collected from the outskirts of the city—have been removed this time, just as the city’s urban development has displaced those who once wore them (figure 11). Created in 2008 (the year of Beijing Olympics) and shown at the 2008 Shanghai Biennale, Flying Machine fused a tractor, sedan, and airplane in three directions, symbolizing the convergence of different eras in China. Yin once wrote in the book, “This is also the reality of China,” a line excluded from the current didactic (figure 12). Instead, Yin added that Flying Machine is “a place where people enter and interact freely.” Ironically, the only conversation that took place was me reminding another visitor, “oh, we are not allowed to sit on that.”

A fourth direction, Piercing the Sky, connects Flying Machine and Sky Patch (figure 6). Yin explains in the didactic that this work “expresses mankind’s yearn for exploring the outer space, and symbolizes the courage to break through the sky limit, serving as a manifestation of transcending the dimensions of reality.” Yet the nearby Tower of Sound (2023-2024), which has a sharp-ended shape of broadcasting towers similar to Piercing the Sky, hints at another side to this cheerful, forward-looking narrative (figure 13).

Despite its name, Tower of Sound is silent. Its didactic label explains that the nylon stockings encasing the sharp objects “do not vibrate to produce sound, and even absorb sound.” And this tension gives “the silence of the silence enough strength.” This evokes Yin’s earlier Weapon series, in which she also wrapped sharp-ended towers with clothing to suggest “[b]eneath the warmth lies violence and brutality. […] In our real lives, many brutal realities and violent threats are concealed beneath warmth and gentleness. [... When] revealed, it appears even more brutal and violent through the contrast.” In Tower of Sound, this muted violence surfaces as another Broken Tongue, contributing to the quietness that pervades Piercing the Sky.

Structured Space in Hall 1

Once we move into the main exhibition hall, two contrasting materials—soft cloth and solid walls—divide up the space and merge in white (figure 14). This duality is reflected in many of Yin’s works, such as Saliva (2024) where a Klein Bottle contains human saliva (figure 15). The bottle’s continuous outside/inside space alludes to the question of public versus private ownership over one’s body fluids. For example, who owns the saliva taken from people for mandatory daily PCR testing in China during the pandemic? No trace of this daily routine can be found nowadays. Yin’s Chance and Inevitability (2024) focuses on a fishing pole she used daily starting in 2020 to open her studio window. Putting back the pole every day for over four years has left visible scratch marks on the wall (figure 16). Did the daily rubbings of nasal swabs leave any marks?

Initially, the missing references (like the never-mentioned PCR testing and the removed “reality of China”) confused and disappointed me. I questioned whether Yin Xiuzhen had lost touch with realities. Yet re-reading her book gave me confidence that she must have heard the same silence as I do. The immaculate white cube seems to hide aspects of the last four years, much like the shiny glass in Yin’s new Black Hole series (2018-2024) on the other side of the hall. Previous iterations of Black Hole used shipping containers and neon lights to create diamond shapes that symbolize vessels of desire, whereas Black Hole 3 and Black Hole 4 here are made of roughly cut glass. They reflect the viewer while pulling us into a dark emptiness, the work Tunnel (figure 17).

In this darkness, a sound emerges. To investigate its source, we need to understand how Piercing the Sky is arranged in the PSA’s open floor plan, which does not follow a strict linear path (figure 18). Instead, the exhibition is ambivalent about its entrance and exit, which is further disrupted by the numerous Exit (2024) signs. This ambiguity allows different visiting directions and perspectives. On top of that, a belt of smaller, partly divided rooms wraps around a large central room. This circular layout, accompanied by Yin’s references to Buddhist classics in the didactics, reminds me of the way people admire Buddha statues in Mogao Caves of Dunhuang. Often guided by monks, people circle the central statue while chanting sutras. Here, the dark central room we circle around holds Golden Horn, an audio installation playing the “golden record” of sounds from Earth carried by Voyager 1 (figure 19). This is the sound that we hear in Tunnel. Centering these collective sounds, Yin seems to advocate for something against the prevalent silence of the Broken Tongue.

Back in the dark Tunnel, the only clue is the faint sound of the Golden Horn. Following the sound, we stumble around to find a small lens in the wall, a reversed telescope that pushes the magnificent central room away, making it look distant and small (figure 20). If all we have is the courage to “break through the sky limit,” what exactly awaits us on the other side?

Exiting the show, I ride an escalator to the top floor. From above, I finally see the other side of Sky Patch—hundreds of tight wires suspending the clothes, all meticulously stretched. The labor of patching the sky is finally visualized (figure 21). On the top floor, a wooden-deck balcony hosts Kozo Nishino’s On Becoming the Wind from the 9th Shanghai Biennale (2012) (figure 22). Under the pink sunset, a breeze stirs the great mechanical bird to life. The bird starts to flap its wings with startling freedom, yet it remains silent. Across the street, I glimpse office workers, absorbed at their desks. I wondered if they, too, can hear the Broken Tongue.

1. Hou Hanru and Yin Xiuzhen, “Interview” in Yin Xiuzhen, eds. Hou Hanru, Wu Hung, Yin Xiuzhen, and Stephanie Rosenthal, Contemporary Artists (London New York: Phaidon, 2015), 15, 19, 22, 34, 37, 44.

2. Yin Xiuzhen, “About Clothes, 2000-02” in Yin Xiuzhen, eds. Hou Hanru, Wu Hung, Yin Xiuzhen, and Stephanie Rosenthal, Contemporary Artists (London New York: Phaidon, 2015), 126.

Yin Xiuzhen: Piercing the Sky

09/11/2024 — 16/02/2025

https://www.powerstationofart.com/whats-on/exhibitions/yin-xiuzhen-piercing-the-sky

Figure 1. Karen Smith, “Yin Xiuzhen: Early Works and the Mindset and Opportunities for Contemporary Art in the 1990s,” PSA Shanghai, Feb 16, 2025

Figure 2. Yin Xiuzhen, Broken Tongue, 2024, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 3. The Heritage Architecture Plaque for PSA Shanghai

Figure 4. Didactic panel for Broken Tongue, Yin Xiuzhen, 2024, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 5. Hou Hanru, Wu Hung, Yin Xiuzhen, and Stephanie Rosenthal, eds. Yin Xiuzhen. Contemporary Artists. London New York: Phaidon, 2015.

Figure 6. Yin Xiuzhen, Flying Machine, Piercing the Sky, and Sky Patch, installation view at PSA Shanghai, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 7. Yin Xiuzhen, Sky Patch, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 8. Yin Xiuzhen, Washing River, 1995, performance documentation on view at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA), photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 9. Messages from donors for Action and Reflection in Shanghai, Yin Xiuzhen, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 10. Yin Xiuzhen, 1080 Breaths at PSA Shanghai, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 11. Metal skeleton of Flying Machine, Yin Xiuzhen, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 12. Didactic panel for Flying Machine, Yin Xiuzhen, 2024, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 13. Yin Xiuzhen, Tower of Sound, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 14. White curtain and wall at Piercing the Sky, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 15. Yin Xiuzhen, Saliva, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 16. Yin Xiuzhen, Chance and Inevitability, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 17. Black Hole 3 at the end of Tunnel, Yin Xiuzhen, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 18. Floor map of Piercing the Sky.

Figure 19. Yin Xiuzhen, Golden Horn, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 20. The lens side of Golden Horn, Yin Xiuzhen, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 21. Tight wires suspending Sky Patch, Yin Xiuzhen, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 22. Kozo Nishino, On Becoming the Wind, 2024, photography: Anqi Li.

Cao Fei: Tidal Flux

Anqi Li

For Cao Fei, the divide between dystopia and utopia is not the point—she is more interested in documenting an alternative narrative of “contradictions that do not resolve”.

The first thing I see at Tidal Flux is an enormous octopus standing beside the title wall (figure 1). It is not labeled in the exhibition floor plan, yet it somehow connects everything within. Its physical presence with artificial coloring reminiscent of the virtual world, and untouchable softness guarded by ropes, evoke a sense of both attraction and restriction. Perhaps a nod to Donna Haraway’s Making Kin? This octopus encapsulates Cao Fei’s artistic approach—humorous and empathetic. Her humor sharpens her ability to capture life’s ironies through unexpected juxtapositions, while her empathy drives her to critique relentless systems and attune to the complex emotions of those entangled in them.

At the Museum of Art Pudong (MAP), the three co-curators create an integrated space that sustains this flux in two ways. First, by constructing a plastic/metal/glass industrial structure that blends artworks with their surroundings (figure 2), they establish a coherent universe within the museum. Second, by incorporating Shanghai’s landmarks, they blur the boundary between the exhibition and the world outside.

Building A Universe Inside

Many of Cao Fei’s video works exceed 20 minutes, the unspoken limit for exhibiting videos. Some are even longer than feature films—a challenge for audiences in an age of social media’s short video format. Yet, the curators did not compromise. Instead, they created immersive setups for each work, significantly enhancing the visitor’s experience.

My previous encounter with Cao Fei’s work was at Connecting Bodies – Asian Women Artists at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. There, Live in RMB City (2009) was displayed on a monitor with headphones in a group show of over 130 works (figure 3). Watching it overseas already felt like voyeuristically peering into China’s cyberpunk dystopia/utopia. The setup reinforced the illusion that technology’s influence is confined to cyberspace, to China—as if those outside RMB City remain unaffected. But is that true?

At Tidal Flux, the curators implicate us in a more physical experience through elements like Screen Autobiography’s (2023) overflowing green screens (figure 4), the balance ball chairs in front of Meta-mentary’s (2022) (figure 5), the sponge pool underneath East Wind’s (2011–2024) (figure 6), Nova’s (2019) folding theater seats (figure 7), Asia One’s (2018) canteen chairs (figure 8) and delivery truck (figure 9), and karaoke booth inside HX Project (2019–2020) (figure 10). This approach highlights the material impact of events documented in the videos, especially for virtual projects like Screen Autobiography (2023). It challenges the assumption that the virtual and physical exist separately: Social media already shapes how we look and behave, and online orders culminate in real-world deliveries. Moreover, the curatorial playfulness in integrating these elements suggests the artist and curators likely found joy in conceptualizing them. Yet, it should be warned that this same playfulness risks turning the exhibition into a theme park or a movie set, where spectacle overshadows meaning (figure 11).

Bringing in the City

The second strategy—incorporating Shanghai’s urban landscape—also contributes to the exhibition’s impact. Shanghai, the city with the highest GDP in China, is an apt setting for reflections on wealth and power. As RMB (i.e. Chinese currency yuan) accumulates in Shanghai, the words printed on a window—“MY CITY IS YOURS, YOUR CITY IS MINE”—prompt us to reconsider the relationship between the virtual and physical RMB Cities (figure 12). Even as the immersive RMB City setting in the galleries dissolves the boundary between technology and real life, the VR telescope installed in the hallway paradoxically reinstates it (figure 13).

Using MAP’s prime location, the telescope directs viewers toward the Oriental Pearl Tower, Shanghai’s emblem of economic development. Yet, when we try to view it through the telescope, we become disoriented, seeing only RMB City’s digital landscape instead (figure 14). Steering the telescope, we cannot locate the actual tower before us; instead, we are navigating the VR world. By showcasing the physical city with the virtual in one work, Cao Fei underscores the blurred yet persistent line between reality and simulation—one that technology has yet to completely erase. But as VR and AI continue evolving, how much longer will this line hold?

Another city landmark integrated into Tidal Flux is the Bund, a region that shows a significant European influence with its Gothic, Baroque, Neoclassical, Romanesque, Art Deco, and Renaissance style architecture (figure 15). If Tidal Flux’s last touring site, UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, was a fitting site for the Beijing-based HX Project, which documents the demolition of a community theater, its presentation at MAP Shanghai introduces a new layer of meaning to it. A single wall separates HX Project from the twice-emphasized Bund’s magnificent skyline in the Mirror Room—once through its French windows, then again in its pristine mirrors (figure 16 and 17). Tourism-driven, the Bund’s colonial-era architecture has outlasted China’s revolutions, rebranded as a symbol of Shanghai’s historic grandeur. Stripped of its colonial history, it now stands as a spectacle of modern aesthetics. Meanwhile, neighborhoods like Hongxia—the protagonist of HX Project—and countless others in Beijing and Shanghai have ended up in ruins, giving way to more skyscrapers (figure 18).

In this juxtaposition of preservation and demolition, spectacle and erasure, history and progress, the Bund and Hongxia become symbols of the contradictions that Cao Fei’s work continuously exposes. Just as the Oriental Pearl Tower disappears in the VR telescope, the material past of cities is often rewritten or erased, leaving only reflections of what once was.

Curator Yang Beichen observes, “Cao Fei’s work creates a nexus of archival files, objects, both factual and fictional, imaginary and historical. They reflect off and resonate with each other.” In Tidal Flux, these reflections extend beyond the exhibition walls, providing us with “an alternative reference” to the flux between past and present, physical and virtual, humor and critique (figure 19).

1. Donna Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991), 149.

2. Abdul Muqeet Waheed, “Best Places to Visit in Shanghai – China Travel Guide with Video,” Top Travel Advice, accessed March 2, 2025, https://toptraveladvice.com/blog/best-places-to-visit-in-shanghai-china-travel-guide/.

Cao Fei: Tidal Flux

22/06/2024 — 09/02/2025

https://www.museumofartpd.org.cn/en/exhibitiondetail?id=155#profile

Figure 1. Octopus at Cao Fei’s Tidal Flux, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 2. Entrance of Cao Fei’s Tidal Flux, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 3. Cao Fei, Live in RMB City, 2009, on view at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA), photography: Anqi Li.

Figure 4. Cao Fei, Screen Autobiography, 2023, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 5. Cao Fei, Meta-mentary, 2022, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 6. Cao Fei, East Wind, 2011–2024, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 7. Folding theater seats for viewing Nova, Cao Fei, 2019, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 8. Canteen chairs for viewing Asia One, Cao Fei, 2018, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 9. Delivery truck as part of Asia One, Cao Fei, 2018, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 10. Inside the karaoke box as part of HX Project, Cao Fei, 2019–2020, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 11. Entrance to HX Project, Cao Fei, 2019–2020, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 12. VR telescope of Live in RMB City, Cao Fei, 2007–2022, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 13. Cao Fei, Live in RMB City, 2007–2022, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 14. View inside VR telescope of Live in RMB City, Cao Fei, 2007–2022, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 15. The Bund viewed from the Mirror Room at MAP, Shanghai, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 16. The Mirror Room is one wall away from HX Project (no. 12 on the floor map).

Figure 17. The Bund reflected in the mirror at MAP, Shanghai, photography: Anqi Li

Figure 18. Postscript of Hongxia shares the final chapter of the Hongxia Theater, Cao Fei, 2023

Figure 19. Final statement by Cao Fei at Tidal Flux at MAP, Shanghai, photography: Anqi Li

100年後芸術祭:山武100年後芸術祭

タニグチアスカ

土地の固有性自体にテーマを持たせるのではなく、地球上の全ての場所に普遍的に訪れる「百年後」を現在の風土から読み取ろうとするテーマ構造はあたらしく、異なる設置場所の作品に多様に機能していた。

100年後芸術祭は千葉県内の内房総5市(市原市・木更津市・君津市・袖ケ浦市・富津市)と、市川市、佐倉市、栄町、山武市、白子町それぞれで開催される計6つの芸術祭で構成された複合型芸術祭である。百年後を「共創する場」として機能する芸術祭として実施された。

筆者が足を運んだのは九十九里浜を擁する山武市で開催された山武市百年後芸術祭だ。

山武市百年後芸術祭では柴原エリア・山武市歴史民俗資料館・食虫植物群落・九十九里浜エリアの4つのエリアをバスで巡回することができる。大きな特徴は、作品とは別に地元の文化施設や自生する生態系に触れる機会が組み込まれていたことだ。食虫植物群落で、山武に暮らす人々と湿地を覗き込みながら食虫植物の仕組みを教わったのは記憶に新しい。訪れた場所について学ぶ経験は、作品の鑑賞にも深みを与える。柴原エリアでは酪農の発祥地としての千葉県の歴史に重なるように、小林清乃の「コエロギネの解剖学」が畜舎で流れていた。乳牛がいまはもう一頭もいない場所で、干し草の上で聴く虚しさが忘れられない。

光岡幸一に「いい道」「あっち」など指されながら、最後に九十九里浜エリアで背の高い草むらを掻き分けて浜に辿り着いたとき、「これが百年後の景色か」と思ってしまった。垂れこめる分厚い雲、砂場に打ちつける波。灰色の浜には点々と作品が位置し、その周りに人がまた点々と集まっているのが見える。鮮やかなSIDE COREの作品がとりわけ目立つ。振り返ると草むらのせいか地形のせいか、都市部のビルの頭ばかりが見え、現代の技術がすべて無に還ったような景色が広がっていた。芸術祭とツーリズムの組み合わせについて「非日常性を利用している」という言説の使用は珍しくないが、非日常として「未来かもしれない場所」を経験したのは初めてだった。遠く百年後へ向けて発信されている、橘田優子の「Letter to you」が百年後からみたときの過去―現在の私たちによって観測されている。

この芸術祭に居る限り私たちは、フィジカルな風土の上で現在を見つめながら「過去を見る」営みに参加すると同時に、「未来から、過去としての現在を見る」視点に晒され続ける。そうして初めて「過去として見ること」の暴力性に気づくのだ。私があの九十九里浜で退廃的な風景に感じたのは、無意識に投射された視線によって「過去になってしまったもの」への弔いだったのかもしれない。芸術祭をあとにしてもなお、来場者の意識を普遍的な過去と未来に拡張する稀有な試みだったと感じる。

山武市百年後芸術祭

2024年4月27日(土)〜5月19日(日)

https://100nengo-art-fes.jp/sammu/

橘田優子《Letter to you》、2024、インスタレーション、展示風景、撮影:タニグチアスカ

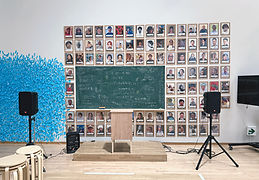

What does it mean to be “democratic?”

Yoshiaki Kaihatsu: ART IS LIVE – Welcome to One Person Democracy

Able Zhang

Once entering the exhibition space of ART IS LIVE – Welcome to One Person Democracy, audiences will find themselves in an exhibition that is less a static display of objects and more a living social experiment, or even a participatory amusement park. The artist Yoshiaki Kaihatsu has built a practice around engaging everyday people in the creation of art. His method imagines art and society as something activated by individual activism. Just like what the exhibition’s title is calling for, Art is Live, the artwork here comes alive only through audience interaction and participation, with each one’s actions helping complete and shape the meaning of the work.

The exhibition is packed with participatory projects that rely on audience engagement to be fully realized with a diverse range of intentions. For instance, every participant will be given a welcome kit before entering the exhibition space. They can choose whenever to open the kit and complete the mission. (I think mine was to look at a piece and pretend to be moved and inspired with a sound “ummmm”.) This work is only completed when they execute their missions outlined on the mission card. Therefore, inside of the gallery space, even if someone appears to be uninvolved, they might be actively fulfilling their own mission. Another example would be the 147801 series, in which participants can take home any wooden object, mostly construction-material-like pieces with paints and nails, displayed on the shelves. However, it can only be considered artwork after they display and photograph it at home with whatever position they prefer. They must then send the photo data back to the artist and give away the authorship of the photo as an artwork to Kaihatsu, for him to challenge Picasso’s lifetime record of 147800 works.

Yet why making every audience/participant active in the art museum? What does it mean to be individually actively-engaged in Kaihatsu’s mind? These questions are connected with Kaihatsu’s guiding concept of “one-person democracy,” a term coined by the late arts administrator Osamu Ikeda to describe how one individual’s action can cause change in others. The paradoxical phrase suggests that democracy fundamentally begins at the level of the single yet empowered person, and this exhibition illustrates this very idea by empowering every audience/participant to speak up, make choices, and leave their mark inside and outside of the exhibition space. Many works take the format of open-ended scenarios that require public input yet drawing no conclusions, effectively making every participant a co-creator of Kaihatsu’s work.

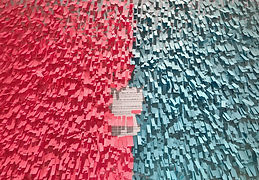

In Vote YES/NO in MOT piece, a wall display presents provocative and controversial statements on contemporary issues, and participants respond by casting a blue post-it note for “yes” or a pink one for “no.” They collectively register their agreement or dissent on statements like “I don’t think we should accept immigrants” or “I don’t think female and male should have equal rights.” The result is a visual presentation of divided public opinion—the total pink and blue votes are nearly even, regardless of the questions taken. On one hand, this constantly changing result thereby suggests the “powerless feeling” of an individual’s voice in a deeply divided and contradicted neoliberal society, yet, on the other hand, pointing out that public opinions rely on each one of the voices. Just as a ballot is meaningless until a voter casts it, the wall will remain conceptually and physically blank until participants contribute their votes and have their individual voices heard.

While deeply playful, the exhibition doesn’t therefore draw a line from socio-political themes. Kaihatsu’s interactive works highlight issues in current society and invite the participants to respond, thereby collapsing the distance between art and everyday politics. The Vote YES/NO in MOT wall’s prompts about immigration and gender, for example, directly address real public debates. By asking participants to take a stand on such statements, the piece transforms the gallery into a real stage of civic discourse. It is an exercise in free expression as well as a self-reflective mirror—seeing how others have voted can trigger dialogue and internal reflections about these contentious topics. Furthermore, it makes people rethink their process of drawing conclusions and jumping into a specific standpoint since some questions might not be a simple yes-or-no or black-and-white type of question. What lies in between the blue zone and pink zone on the wall becomes truly essential behind these questions. Such work embodies Kaihatsu’s view that “democracy is ... the chain reaction where one person’s specific action causes other people to act.” Here, a single participant’s post-it note can prompt the next person’s response or even action, setting off a domino effect of engagement in democracy.